Understanding Movement Dysfunction

Understanding movement dysfunction is an ever illusive topic. I can see myself in my 70′s still pondering the best ways to try and understand, categorise and screen for movement dysfunction (hopefully in a warm country!!). However, striving for the best framework to assess and treat is something we all have to do, otherwise we would have a basis to work. So where does movement dysfunction come from?

As best as I can work out at the moment there are 3 fundamental aspects that drive movement dysfunction:

- The Range of Motion

- The Speed of the motion

- The Sequencing

This for the most part this comes from learning with Gary Gray and Dave Tiberio. Though also, the development of the process has come from working with John Hardy.

1. Range of Motion

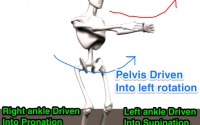

Initially, I was taught that there are 2 sides to this coin…too much range or too little range. Successful movement is challenged when there is excessive/limited motion at a particular joint or plane of motion. For example, if there is limited dorsiflexion range at the right foot (for what ever reason for now), the body will have to choose a strategy to cope with that limitation. That may mean an early heel lift, a foot that spins out or many other possible changes to gait (for example). At a local level this may or may not have local consequences, however, in both of these examples the hip will also have a choice to make. If the heel is lifting early the knee will have to flex limiting the hips ability to extend and load in the sagittal plane. Also, if the foot spins out the hip will be unloaded in the transverse plane at a time when you really want it to load strongly into internal rotation.

The one thing I would add to this excessive/limited ROM thought process may be to add that it makes a big difference not just how much range, but where in the range the motion takes place. For example, if the joint starts near end range there may not have any more motion to give. This may give a real challenge to the muscles that would normally be loaded in that motion.

I guess this links into posture. If for what ever reason you are already in the position it’s very difficult to create motion and therefore load in that motion. Imagine trying to triple extend into an explosive jump, but starting standing upright! It’s not going to result in a great jump, you have load into triple flexion first. This is a global example of course, but in my head I’m seeing this breaking down into single joints and planes at that joint that is the trigger for movement dysfunction.

The other thing I would add to the range of motion discussion would be something I have learned more over the last year or so, which is ‘why is the range limited?’ Is it a structural thing, or is it a motor skill issue? If it is a structural thing, is it something that can respond to treatment or is it something that is anatomical and needs strategies to work around the limitation? If it is a skill issue, what are the strategies needed to teach this individual the movement skill they need?

This last point is something I am really keen to explore over the next year or so. I mentioned yesterday how I am listening to a book about the psychology of sports performance and I really see a clear link into teaching skill. Even if that skill is not sports performance, it is still the skill of movement. I’ve written about my belief in using subconsciously driven motion many a time…and the more I read the more I find that backs that up.

OK…it’s fair to say I was planning on writing about all 3 points in this post and I’ve reached my word limit having only made it though the first!! So I’ll have to finish off next time (or two!)….the next post I’ll take a look at the how movement dysfunction is affected by the speed of motion.

Physioblogger